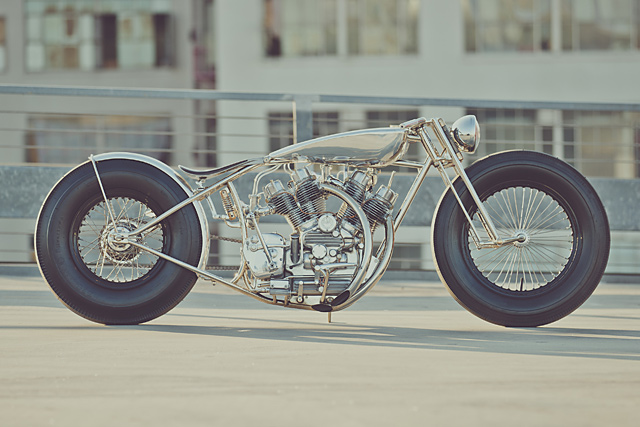

‘Maxwell Hazan’ is a name that needs no introduction. As s two-time winner of Pipeburn’s Bike Of The Year award, he’s one of the few builders globally that could lay claim to the title of ‘world’s best’. So what does a guy with so much raw talent, fabrication ability and vision do next? Whatever he damn well pleases – that’s what. And what Max pleases in 2015 is to take two Royal Enfield 500cc engines, enlist the help of a certain Mr Aniket Vardhan to magic them into a single 1000cc V-twin, and then construct a bike around it that just might be the best-looking custom bike we’ve ever seen. Excited? We sure as hell are. Here’s Hazan Motorwork’s latest, ‘The Musket’ Royal Enfield V-twin.

With our excitement rendering us barely able to speak, we began by proposing marriage to the guy. After his twelfth refusal, we cottoned on and asked Max about the bike. “The Musket is a project that I have wanted to build for years; even before I built motorcycles for a living, I used to drool over this hand-made gem of an engine. It’s essentially where the build started. It’s a work of art that was hand-carved from a block of wood, hand-cast at a foundry and then hand-machined, all by the amazing Aniket Vardhan to make this, the 1000cc Musket V-twin engine.”

Thinking back, Max felt there was a certain amount of fate to the build. “I was approached by an open-minded client at exactly the same time that Aniket had just finished development on his latest engine and was ready to part with it. I went through four different sets of tires before settling on the huge BF Goodrich Silvertown car tires you see here. The engine is truly massive, making the big frame absolutely necessary. This in turn dwarfed standard motorcycle tires and, well, you get the drift.”

“The tires, wheels and headlight are the only pieces that were purchased. Every other part was made by hand.”

If the world’s most beautiful music was rendered in metal, it would look like this

Of course if nothing is pre-made, you can create every part exactly how you imagine it – especially if that imagination is one of the motorcycling world’s most vivid. Following the engine’s lead, the shape of the tank, the angles in the frame, the pipes and everything else was mocked up, tweaked, scrapped and redone until their lines, shape and position were perfection incarnate.

As always, Max started by mounting the engine on his workbench and secured the wheels fore and aft. He then sketched the bike’s initial shape out on a giant sheet of paper and hung it up behind. Designing the bike at full-scale allows Max to see how each part fits exactly with the next and how the bike’s final proportions will appear. It also gives him something real to measure off of when he’s rough-cutting the raw material.

“I tend to gravitate toward the minimal side of things, so I don’t like cables and wires. But if they have to be there, then I try to make them interesting to look at. I also wanted to make the handlebars completely clean, so I ran an internal throttle cable through the 7/8″ bars and went with a hand shift and clutch to clean up the lower controls. I decided to cut into the primary drive, run it dry and move everything outwards to make room for a disc brake in the transmission. Surprisingly, it works great. This also allowed me to simplify the rear wheel, too.”

The bike has a very small battery made from an Antigravity unit that Max cut up and rearranged to fit inside the bespoke fuel tank. The rest of the ignition and electronics were housed under the engine for better airflow and less exposed wiring. “I have found time and again that ‘simple’ is the usually the most complicated to make,” Max laughs.

The tank and fenders were all shaped from .16 or .18 gauge 6061 aluminium, and the frame is all 7/8-1 1/4″ steel tubing with varying wall thicknesses depending on the specific application. The tank’s shape was intended to showcase the motor, so Max wanted something that flowed along with the design but didn’t obstruct the view of the cylinder heads and rockers. He also wanted to challenge himself and set his mind on making a thin, polished aluminium tank and fender from scratch. “I had to make several of each,” says Max, “as the thickness doesn’t leave much room for error. You’d be kidding yourself if you think you’re going to nail it on the first try. No way.”

“The forks were another first for me; it was an idea I had where the moving parts of the springer mechanism would be in tension instead of compression, allowing me to use much thinner steel. All of the shocks were made from bearing bronze and use sections of fork springs with smaller valve springs inside them.”

Max didn’t set out to do another wood seat, but once he’d made the call, he decided to make it as comfortable as possible this time. It’s a beautifully-aged piece of walnut, coated in around 15 layers of polyurethane lacquer and then polished to within an inch of its life.

“I wanted it to be finished like a Steinway Piano; just make sure you hang on when you twist the throttle.”

Max prays at the chrome altar

And as much as we’d like to tell you from first-hand experience what it was like to ride, Max was adamant that he be the sole jockey before the masterpiece was handed over to its new owner. “It’s much quieter than you would imagine with the pipes that I made for it, but it pulls like a particularly angry tractor. Obviously, the tires are square and your cornering skills do need to be adjusted a little to compensate, but all-up it’s an amazingride. With about 55hp and a 6.5:1 compression ratio it’s not an overly fast bike, but speed was not on the agenda for this one.” Whatever Max’s agenda, you can be sure of one thing – when this New Yorker puts his mind to it, amazing things happen.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét